Although honeybees can survive cool body temperatures for a long time, they keep the center of thee hive and their brood at temperatures above 30°C. The temperature plays an important role in the development of the brood and the division of labour of the bee colony. Therefore, a bee colony spends 40% of its energy reserves on thermoregulation.

Airco and ovens

Through their behaviour, worker bees control the incubation temperature of the brood. In particular the capped brood is kept between 32°C and 36°C. When this temperature is exceeded, the bees start cooling the hive and the brood. The bees function as real air conditioners: It has been shown that a bee colony could even survived on a lava field with temperatures above 70°C! In order to lower the temperature, the bees perform a organized fanning of the wings; some bees place themselves at the hive entrance and increase the air circulation in the hive by fanning air currents of up to 60 L/min into the hive. Further, the bees carry water into the hive, which is distributed in the form of small droplets and placed on the cell walls of brood cells. The evaporation of the water creates a cooling effect and the moisture prevents the larvae from drying out. If these behaviors cannot lower the temperature sufficiently, the bees will form a cluster outside the nest and only the bees which are needed to manage the water input and fanning will remain inside[1].

On the other hand, when the brood temperature is too low, the workers generate heat with their flying muscles. They press their thorax directly onto the capped brood cells or use empty cells in the brood nest to warm the surrounding cells which contain larvae. The flight muscle of honeybees is 20% of their body weight, through shivering or muscle tremors these muscles, they can increase their metabolic rate by 25 times. This increase in muscle activity generate lots of heat. In comparison, muscle tremors in mammals produce only a 2 to 5-fold increase in their metabolic rate. Honey bees are therefore true heating ovens! Additionally, bees can reduce the heat loss of the brood by forming a cluster around it[1].

Warmth makes smart

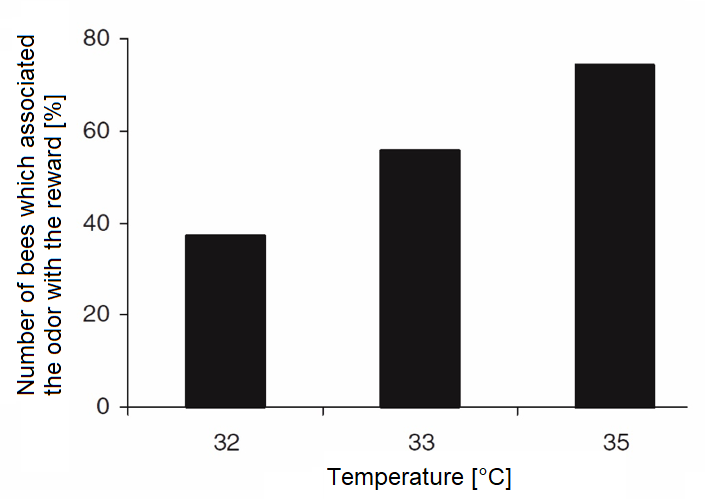

Several scientific studies have investigated how the temperature during the development of larvae affects their behaviour as adult bees. To test this, the brood was kept in incubators with constant temperatures between 32 and 35°C. These experiments have shown that warm temperatures have a positive effect on the development of the nervous system[2]. Larvae exposed to warm temperatures during their development showed better learning behaviour than larvae exposed to cooler temperatures.

The learning ability of honeybees can be measured with the Proboscis Extension Reflex (PER). Here, bees are presented with sugar water in combination with a odor. If the bees learn to associate the odor with the reward, they will stick out their proboscis (the tongue of the bees) as soon as they smell the odor. In contrast, bees with weak learning abilities, do not react to the scent. While about 70% of the bees that had developed at 35°C reacted to the odor, the bees with a development temperature of 32°C reacted less than 40% (Figure 1)[3].

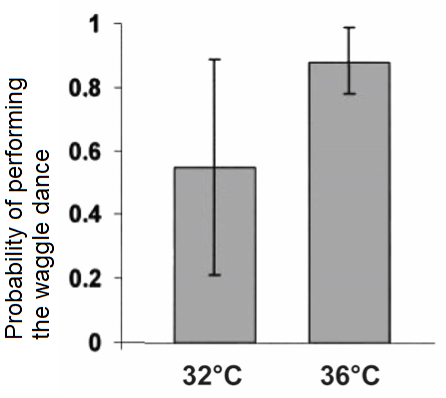

In addition to the learning ability, the brood temperature also influences behaviors such as cleaning, foraging and dancing of adult bees. For example, bees that have developed at warm temperatures are more likely to show cleaning behaviour in the hive and leave it earlier to forage for pollen and nectar. They are also more likely to perform the waggle dance and also dance for longer periods (Figure 2). Based on these results, it is suspected that brood temperature plays an important role in regulating the division of labour in bee colonies[4,5].

Cuddling against the cold

At body temperatures of around 10°C, the bees fall into a chill coma and die after a few hours if they cannot warm up again. This is why in winter, the colony forms a so-called winter-cluster. In the center of this winter cluster, high temperatures are maintained. Even at an outside temperature of -20°C, temperatures of 25-35°C were measured in the center of the winter-cluster[6]. This allows bees to survive long periods of below-zero temperatures. To maintain these temperatures, however, the colony must be of a certain size (Table 1). In the winter cluster, the bees arrange themselves in layers in order to increase isolation. The bees in the outer locations are repeatedly replaced by bees from the interior. In the center of the cluster is the queen, optimally protected from the cold. If the temperature in the beehive falls below 10°C, the bees begin to shiver with their muscles and warm up the winter cluster again. This allows the hive to be warmed up again to over 30°C, making the stored honey liquid and easy to consume. These “heat peaks” was first documented by HOBOS in 2012 on the basis of temperature measurements on the Würzburg bee research hive[7]. Passageways in the winter cluster allow for air circulation and can be narrowed and extended to regulate the temperature[1].

![Table 1: Probability that a bee colony will survive the winter depending on the colony strength[8]. Table 1: Probability that a bee colony will survive the winter depending on the colony strength[8].](/web/image/7519/Ueberlebenswahrscheinlichkeit.png?access_token=837a811f-5d96-4cec-9e21-b9f53f479d5c)

Optimally adapted everywhere

The different breeds of the European honey bee show adaptations to the local climate. The European dark bee (Apis mellifera mellifera) more resistant to cold than other subspecies living in warmer regions (A. m. intermissa, A. m. scutellata, A. m. lamarckii, A. m. capensis)[1]. It has also been shown that there are also adaptations to warm climates. The honeybee subspecies of Yemen (A. m. yemeni) has a better heat tolerance than the Carniolan bee (A. m. carnica)[9].

Literature

1 Southwick, E. E. & Heldmaier, G. Temperature control in honey bee colonies Bioscience 37, 395-399, doi:10.2307/1310562 (1987).

2 Groh, C., Tautz, J. & Rossler, W. Synaptic organization in the adult honey bee brain is influenced by brood-temperature control during pupal development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101, 4268-4273, doi:10.1073/pnas.0400773101 (2004).

3 Jones, J. C., Helliwell, P., Beekman, M., Maleszka, R. & Oldroyd, B. P. The effects of rearing temperature on developmental stability and learning and memory in the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Journal of Comparative Physiology a-Neuroethology Sensory Neural and Behavioral Physiology 191, 1121-1129, doi:10.1007/s00359-005-0035-z (2005).

4 Tautz, J., Maier, S., Groh, C., Rossler, W. & Brockmann, A. Behavioral performance in adult honey bees is influenced by the temperature experienced during their pupal development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100, 7343-7347, doi:10.1073/pnas.1232346100 (2003).

5 Becher, M. A., Scharpenberg, H. & Moritz, R. F. A. Pupal developmental temperature and behavioral specialization of honeybee workers (Apis mellifera L.). Journal of Comparative Physiology a-Neuroethology Sensory Neural and Behavioral Physiology 195, 673-679, doi:10.1007/s00359-009-0442-7 (2009).

6 Owens, C. D. The thermology of wintering honey bees. Technical Bulltin of the U. S. Department of Agriculture 1429, 1-32.

7 Bee Careful: Bienenvolk im Winter

8 Genersch, E. et al. The German bee monitoring project: a long term study to understand periodically high winter losses of honey bee colonies. Apidologie 41, 332-352, doi:10.1051/apido/2010014 (2010).

9 Abou-Shaara, H. F., Al-Ghamdi, A. A. & Mohamed, A. A. Tolerance of two honey bee races to various temperature and relative humidity gradients. Environmental and Experimental Biology 10, 133-138 (2012).